“What do you mean we’re not from here?” I painfully asked my elder sister Steph.

Even though I’d always felt like an outsider, I had never questioned my roots. There was no reason to. In my eyes, we were like every other Kenyan family. We lived in Shema Courts in Hurlingham next to Yaya Centre, attended French School and occasionally went to church and cinemas.

It wasn’t until I was around nine years old that I started to notice the not-so-subtle differences. We were the only Kashosi in a pool of Maina’s, Oduor’s and other native Kenyan family names. Our Swahili dialect was nothing like what I heard my classmates and churchmates speak. Perhaps most glaring was that we didn’t speak English.

“Steve, we are originally from DRC,” my sister replied and silently watched as my ignorance and innocence faded right before her eyes.

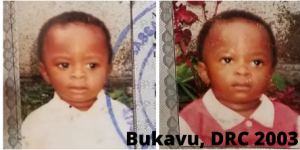

She sat me down and explained that our father was born and bred in the days of unrest in the Democratic Republic of Congo. In 2002, during the Civil war, he got a job in Kenya and carried us along. A few months prior, my mother had passed away while giving birth to my twin brother and I. So our father hoped the move would be a fresh start, away from the pain and despair that comes with war and loss.

She sat me down and explained that our father was born and bred in the days of unrest in the Democratic Republic of Congo. In 2002, during the Civil war, he got a job in Kenya and carried us along. A few months prior, my mother had passed away while giving birth to my twin brother and I. So our father hoped the move would be a fresh start, away from the pain and despair that comes with war and loss.

Not long after learning my family history, dad informed us of his recent transfer to Zambia. ‘A new exciting beginning’, he called it, and I wondered how many more of those we needed. His company was willing to cater for our living expenses, so it was a given we would tag along. I challenged myself to see the move as my father did—an opportunity to reinvent myself. Steve 2.0 would do whatever it took to belong and be accepted here.

The French School in Zambia was nothing like the Kenyan one. The students were mainly white, and most interactions were in English. In a bid to assimilate, my siblings and I purposed to learn the white man’s tongue. Hannah Montana and Justin Bieber became our private English tutors. Dad was quite impressed. He thought English was the gateway to making new friends. It Was Not!

No amount of English made us less black, less African. On the contrary, we were always met with disapproving faces, hushed tones and blatant segregation. Imagine being ostracized for being African in Africa? The only person who ever made me feel welcome from the get-go was Mutale, a young lad from Zimbabwe. Perhaps it was our shared plight that brought us together.

It took a while, but each of us finally found our footing in Zambia. I won favor with most of my classmates with my good grades and superior football skills. Even so, I never formed any budding friendships with the white students. Not for lack of trying, they just never fully embraced me.

Part 2

2 years in, I finally felt like I belonged in Zambia. Kenya had become a distant memory till the day dad announced we had to move back. His contract was up, and there was nothing we could do. I was devastated. How was I to navigate school as the new boy? What of Mutale? All that effort assimilating down the drain.

Fortunately, my fears didn’t match reality. It turns out speaking English can make you new friends in Kenya. But that bliss was short-lived. Later that year, dad moved the whole lot to the Central African Republic (CAR) for a new job. This is where I enrolled in my first high school in 2011.

In CAR, I wasn’t too concerned about making friends and fitting in. I had no headspace to focus on such trivial things when danger loomed all around us. The rebel militia was at war with the government. Is this what it was like for dad in DRC? I pondered. Why did we leave our native soil only to experience the same ills in a foreign land? We only lasted 3 months before dad quit his job. We came back to Kenya, but in less than a year, he got work in Mali.

Life in Mali, albeit safer, wasn’t so far off from that of CAR. We still lived in constant panic and fear. We couldn’t eat any vegetables for a reasonable amount of time because the farms in our area had been poisoned. We had to survive on takeout, and that was a privilege in itself. My heart ached for the common Malian whose options were either dying of hunger or dying of poison.

Our heavily guarded compound became my refuge. The only time I left the safe oasis was when going to school. At thirteen, I had somehow become my father. I was just as closed off and protective of the family as he was. Nothing else mattered except my family’s safety. Not my grades and certainly not friendships.

Ten months later, we eventually came back to Kenya. I was relieved. This would be the last time my father would tag us along for a new posting. Dad thought it wise for us to have a semblance of stability. Since then, whenever he had to travel, an extended family member from DRC would come to watch us.

With stability came a renewed sense of hope for the future. This meant I could dream, hope and want beyond tomorrow. And I wanted nothing more than to belong to something bigger than my immediate family.

I yearned for a place I could call home and a people with whom I shared deep cultural, social and linguistic ties. But, unfortunately, in all the countries I’d lived in, I was yet to fully experience this sense of community.

Ultimately this yearning led me to pursue International Relations at Daystar University. IR has helped me to make sense of it all. I’ve finally learned that true belonging begins with radical self-acceptance. All that time wasted people pleasing could have been better spent finding my authentic voice and self.

The more I engage in this course, the greater my gratitude for all those bittersweet experiences and fresh starts I endured. This must have been what life was shaping me for. Now that I better understand Africa’s history, I’m all the more determined to be part of shaping its future. That said, I’m yet to figure out where home is.