Part 1: Walking my way out of poverty

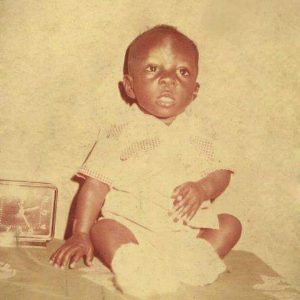

I was born and raised in Korogocho, one of the largest slums in Nairobi. In Swahili, Korogocho means ‘crowded shoulder to shoulder’. That’s how we lived, with my parents and nine siblings all in one room. My dad’s income as a cook at the University of Nairobi and my mum’s as a factory worker wasn’t enough to support us. I realized that life wouldn’t get better just like that. To get out of Korogocho, I had to take my studies seriously.

In reality, it was difficult to study from our small house at the mercy of a frail ‘koroboi’ lamp. I quickly changed strategy and befriended the deputy head teacher’s son. He had all the books I needed. My deputy headteacher, Mr. Kariuki was kind enough to let me study in his home on the weekends; he even bought learning materials for both of us.

In reality, it was difficult to study from our small house at the mercy of a frail ‘koroboi’ lamp. I quickly changed strategy and befriended the deputy head teacher’s son. He had all the books I needed. My deputy headteacher, Mr. Kariuki was kind enough to let me study in his home on the weekends; he even bought learning materials for both of us.

Mr. Kariuki’s son and I made a good team. We always topped our class. I was even among the best students in the final primary exams, so when my dad first told me that he couldn’t afford to send me to high school I was upset. My good friends from church stood in the gap and raised enough to pay for my first term.

The reality at Dagoretti High School was different. Many of my classmates were from well-off families. On visiting days, I enviously watched how they clutched onto shopping bags from their parents. I, on the other hand, was always sent home for not paying my fees and walked around in my ‘mtumba’ (second hand) uniforms with just meagre pocket money for upkeep. With shoes bigger than my feet, I learned a trick or two to make them fit. Newspaper and socks are particularly good stuffing. Every holiday, I walked for about 10km to go and study, from Korogocho all the way to the MacMillan Library in the city center. I knew I was walking my only way out of poverty.

Part 2: Persistence paid off

All the hard work got me into the University of Nairobi, where my dad was a cook. You have no idea how that was such a big relief for me. One of my problems was solved, food. Things were looking up. I always wanted to become a doctor, inspired by my sister who was a nurse, but I ended up studying commerce.

To pay for my upkeep, I hustled my way through uni. From writing other people’s assignments to selling magazines. One time I formed a dance group with my friends called ‘Odugla’. We used to walk 16Kms and back carrying our drums and costumes to dance at Carnivore, an open-air restaurant in the Langata suburb. Not to mention the cold nights just to eke out a living.

After my undergrad, I went right back to Korogocho. While I was trying earnestly to escape poverty and its consequences, I saw my former primary school mates getting sidetracked. Many of them joined gangs; some even got shot. I teamed up with two close friends to help change the dynamics in our community. We launched a beauty pageant called the Miss Koch Initiative.

At the same time, I worked on achieving one of my lifetime dreams: Studying at Duke University. With my humble background, getting a scholarship was my only hope. It wasn’t until the third application that I got into Ford Foundation’s International Fellowship Programme. Being among the 20 students selected out of the thousands of applications was absolute bliss. It felt surreal, but there I was, a boy from Korogocho, going to one of the most prestigious schools in the US for a Master’s in Public Policy. Persistence paid off.

Part 3: Never kick away the ladder

Duke University didn’t disappoint at all. It was all I had imagined and more. I spent most of my University days at the library. The program was intense, and the string of assignments never seemed to end. My presence at the library was so prevalent that the librarian would joke he would name a seat after me.

Most international students dropped out one by one, but I channeled my memories of Korogocho; a reminder that there are no shortcuts to success. My mother taught me that the world has limitless possibilities and opportunities, if only you work hard. That is what I did. For those who made it, graduation was a momentous occasion. I was bursting with excitement when I was handed the certificate. I couldn’t wait to get out there to use the skills, knowledge and experience I got from Duke to build a better world.

Most international students dropped out one by one, but I channeled my memories of Korogocho; a reminder that there are no shortcuts to success. My mother taught me that the world has limitless possibilities and opportunities, if only you work hard. That is what I did. For those who made it, graduation was a momentous occasion. I was bursting with excitement when I was handed the certificate. I couldn’t wait to get out there to use the skills, knowledge and experience I got from Duke to build a better world.

Back home, my childhood in Korogocho informed my passion for the Youth agenda. In 2012, I became Special Advisor at the United Nations Habitat’s Youth Advisory Board. Working with the youth gives me energy and faith in Africa. If anything can pull communities or even the continent out of crises, it will be a new generation of leaders.

Currently, while sitting on the Boards of international bodies such as the United Nations, the World Bank, the Global Diplomatic Forum, and the African Leadership Institute, I still think about Korogocho. In those moments I am back there, in that unforgiving environment; in one of many poor families without access to economic opportunities, health care, good education or the basic essentials to live in dignity. But now, things are improving in Korogocho. There are paved roads, streetlights, water points, footbridges, schools and more small businesses. Much changed there, but I didn’t. I am still that same restless dreamer of the past. I just had to up my ambitions. Nowadays, my hope is to one day serve as the Secretary-General of the United Nations or the President of my country.

Currently, while sitting on the Boards of international bodies such as the United Nations, the World Bank, the Global Diplomatic Forum, and the African Leadership Institute, I still think about Korogocho. In those moments I am back there, in that unforgiving environment; in one of many poor families without access to economic opportunities, health care, good education or the basic essentials to live in dignity. But now, things are improving in Korogocho. There are paved roads, streetlights, water points, footbridges, schools and more small businesses. Much changed there, but I didn’t. I am still that same restless dreamer of the past. I just had to up my ambitions. Nowadays, my hope is to one day serve as the Secretary-General of the United Nations or the President of my country.

On my journey to the pinnacle of power, I keep my dad’s advice at heart. He always reminds me to never kick away the ladder. That is why I started Obonyo Foundation and The Youth Congress to support education for children from poor families, and to give youth opportunities through skills development and entrepreneurship. We must hold the ladder for others.